SPOTLIGHT ON: ALOK JOHRI

Life's Still Yet Most Precious Moments

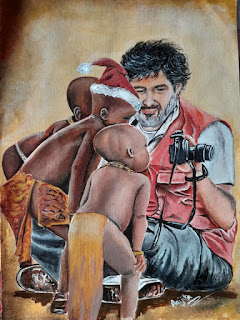

Artist Alok Johri (left) with the show curator Jaiveer Johal (centre) and Tunty Chauhan of Gallery Threshold

Some of my earliest memories of beautiful paintings —

that I found beautiful as a child — were still-lifes. Of course, I didn’t know

then that they were called ‘still-lifes’. Those were images of la vie quotidienne — images of everyday

life that inspire us to see beauty in every little, seemingly inconsequential thing

around us. Europeans, who popularised it, found that beauty most popularly in

things and objects on a dining table. It began as a distinct genre in its own

class in the Netherlands in the 16th-17th centuries, but

some of the most fabulous examples were created all over the European

continent, by artists such as Caravaggio, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Rembrandt,

Vermeer, to name a few. Closer to our times, Vincent van Gogh and Pablo Picasso

are other names whose still-lifes we are all very familiar with.

It wouldn’t be an overstatement to say that almost

every artist, at some point in their career, tries still-life. Modern Indian

masters have done that, with the most striking example, in my opinion, remains

those by F. N. Souza and Jyoti Bhatt, to quote only two examples.

The most striking thing about Johri’s still-lifes is

that they are redolent with emotion; so much so that one knows in an instant

that each of those still-lifes carries some story behind it. It is very

apparent that Johri’s canvases are not just an aesthetic depiction of what he

sees beautiful around him, which, however, remains a primary reason for him to

train his lens on any collection of objects; but there’s more to it.

The large diptych, …Over

Tea, that greets the viewer upon entering the gallery is striking as

evidently there is a story waiting to be told. There is something about the way

the ruffled edge of the tablecloth, an open book with a pair of spectacles on

it, a toppled cup and saucer… “It’s my way of remembering my father and my

mother. The work shows a 20th Century Chamber’s Dictionary, and

below that, the last book that my mother read,” says Goa-based Johri. The

artist, who grew up in Kanpur, studied applied arts at Lucknow University after

switching from fine arts whose entrance test he had topped, upon the advice of

his HoD, the renowned artist B. N. Arya. He went on to work in advertising,

achieving great success, before going solo to travel the country with his

camera.

It's hard to believe that he didn’t train as a painter because the works on display exude depth and gravity of skills honed over years. “I was good at the arts — doodling, drawing, painting — since childhood, and I remember that when I was 8-9 years old, my mother asked me what would I want to be when I grew up, I remember replying that I wanted to be an artist,” shares Johri.

One of a set of 4 works by Alok Johri, titled 'Inheritance'

Just as …Over

Tea captivates with its stark bareness and an overbearing sense of an

active snippet of life frozen in time, his other works, including the small

ones measuring 10 x 10 in., or 17 x 17 in., or 24 x 24 in., draw in the eye

with their zoomed in details of daily life. A

Short Nap, Man with his thoughts,

Mocha, Afternoon, Siesta… and

many more lay bare the most common of our moments on the earth with the

uncommon vision of a painter. A Short Nap,

for instance, focuses on a head turned the other way with the arm of the

subject wrapped around it so as to shield it from day light when someone tries

to take a quick nap in the middle of some work. Similarly, Every Morning shows the corner of a table covered with a tablecloth

and the back rest of a chair pulled out just a bit as if someone has just

gotten up and left the table. It’s a powerful snapshot of a morning which shows

the pithy observation of the painter.

There’s a lot of references to reading in the

paintings, which inadvertently alludes to the artist’s growing up years in an

academic household; both his parents were teachers. During a very enriching

conversation, the artist reveals that placing objects associated with his

parents in the paintings has also helped him reconcile with the difficult

relationship he had with his family. “My father left us in December 1987 as he

took sanyas. We never saw him again.

Years later, when my mother was shifting from Lucknow to Goa with me, I opened

an old trunk of academic books and found my father’s dictionary. My mother was

a voracious reader. So, books find a place in my works,” shares Johri.

While a few of Johri’s paintings took birth in the

recesses of memory in his mind, …Over Tea is the one that gave him closure over several conflicts he had

harboured in his head over the years with respect to his parents. “With this, I

resolved everything with my parents,” he shares at the end of a long, moving

story on his growing up years, which includes a vital landmark — the

disappearance of his father from their lives.

It is this profound experience that has, perhaps, helped Johri translate the minutiae of life on to his canvases, including those that are precious lived moments of all human life, and not just Johri’s, such as Dragon Fruit, Red Banana, Loofah, and Whisper, among others.

The exhibition, on view through October 12, is a

delight because Johri’s paintings start speaking of their stories, of the still

moments that they capture, which are not necessarily the artist’s, but resonate

with the common lives of all of us.

.jpg)

.JPG)